Greifswald is said to be pro-Europe. While the old identify with the East, the young return to links with Scandinavia. Yet, the city has its problems.

By Kit Holden

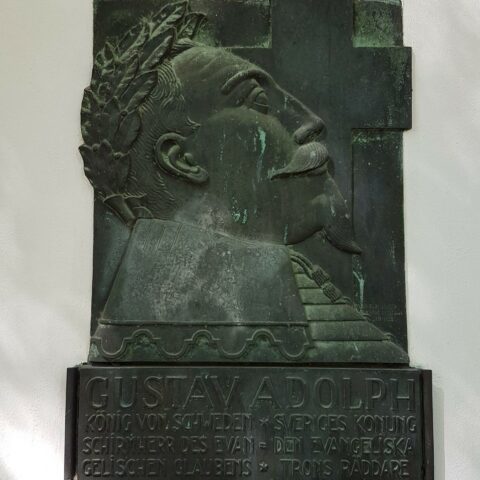

Here’s a question you’ve probably never asked yourself. Where in the world would you find a collection of Danish 19th century art, an exhibition on the history of Estonia, a concert given by southern Scandinavian Sami “Joik” musicians, and a stone relief of Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus, all in the same square kilometre?

The answer, naturally, is in Germany. Or to be precise, in Greifswald, a university town of 61,000 inhabitants in the North-East of Germany, and the next place to host “Wir Sind Europa”. From 7-9 June, the initiative will head north to find out what the citizens of Greifswald think of, and what they can do for, the European idea.

Part of Sweden for two centuries

“Most people here are pro-European,” says Dennis Kley, a communications and philosophy student at the university and a director of the citizens’ radio station radio98eins. Judging by the city’s cultural offerings, he can’t be far wrong. The Estonia exhibition, the Joik gigs and Christoph Müller’s collection of Danish art are all part of the festival “Nordischer Klang” (Nordic Sound), which has taken place in Greifswald since 1992, and celebrates music and culture from across Scandinavia and the Baltics.

Gustavus Adolphus, meanwhile, hangs proudly on the side of the city’s brick gothic cathedral, a relic of Greifswald’s time spent under Swedish rule. For nearly two centuries after the Peace of Westphalia, this now very German city was part of Sweden. Dennis and his fellow students, the joke goes, are studying at “the oldest university in Sweden”.

Gustavus Adolphus, meanwhile, hangs proudly on the side of the city’s brick gothic cathedral, a relic of Greifswald’s time spent under Swedish rule. For nearly two centuries after the Peace of Westphalia, this now very German city was part of Sweden. Dennis and his fellow students, the joke goes, are studying at “the oldest university in Sweden”.

Bringing East and North together

While older generations are, by virtue of 20th century history and the political geography of the GDR, much more likely to identify with Russia and Eastern Europe, the younger inhabitants are returning to Greifswald’s cultural links with Scandinavia, says local blogger Joachim Schmidt. This year, that process seems to have gone full circle, as Nordischer Klang focuses for the first time on Estonia, bringing East and North together.

The festival, incidentally, is just one element of a disproportionately diverse and lively cultural programme. In the summer, the Greifswald welcomes international guests for the Bach Week and for the International Students Festival, while in the autumn, the central market square is taken over by the “polenmARkT”, or Polish market.

“As a city government, we want to promote Greifswald as a tolerant and international town,” says Dr. Sylvia Schönfeld from the mayor’s office. For the most part, she thinks, the people for Greifswald are fully behind that.

Yet for all the Danish art and joyous internationalism, the city has its problems. As East German towns go, this one seems to be booming, but that brings its own trouble, and many here point to a dramatic rise in rents and living costs. Tourism, Schönfeld explains, is still not a major money-spinner, despite the proximity to the Baltic Sea and Greifswald’s famous sons such as romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich or Real Madrid footballer Toni Kroos. The University remains the economic sine qua non of the city, and any cuts to departments or shifts in funding can have real consequences not just for the students, but also for the hundreds of other residents employed by the institution. “The university budget is always a big political issue,” says Dennis Kley.

Along dividing lines

The biggest political issue of all, though, is the university’s name. Under both the National Socialist and GDR regimes, and in the post-Cold War period, it was named “Ernst Moritz Arndt Universität Greifswald” after the 19th century nationalist philosopher. For years, debate in Greifswald has raged as to whether Arndt is an appropriate eponym for a university and a city which presents itself as tolerant and open to the world. Critics point to antisemitism in Arndt’s work, while defenders of the name despair of an over-exuberant political correctness. It is a debate which has taken on the role of proxy for almost all political grievances and differences.

Like many such proxy issues – think Brexit – the Arndt debate can be cast along a number of dividing lines: left versus right, old versus young, East Germans versus West Germans. All of these, Dennis Kley says, are probably too simplistic, but he also concedes that the opposing camps are now so entrenched that genuine, informed debate on the issue is now impossible.

Last April, the state education ministry ruled that the university could change its name to “Universität Greifswald”, dispensing with Arndt, but it is unlikely to be the end of the story. “Whatever the situation is, whether Arndt is there or not, there will always be another petition, another movement against the status quo” says Kley. Again, think Brexit.

“They just want to send a message to the politicians”

If Arndt is the all-consuming political issue within Greifswald’s medieval walls, then there are more existential concerns outside of the city. The surrounding area is characterised, politically speaking, by frustration and a perception of isolation. This may be Angela Merkel’s home constituency, but there are many Pomeranians who are now voting for the right-wing populist AfD. At the general election last year, the party polled at 19.2 per cent in the region.

“Most of the AfD voters aren’t ideologues, they just want to send a message to the politicians,” says Cornelia Meerkatz, a reporter at the regional newspaper Ostsee-Zeitung. She recalls asking one voter on Usedom why they voted AfD, and gawping as they called over their shoulder: ‘Darling! Why did we vote AfD again?”

Meerkatz puts the political disillusionment down first and foremost to the poor infrastructure. Some villages, she says, are not even reachable by bus, and on the island of Usedom, there is a sense that EU development funds flow much more readily into the Polish side of the island than into the German side.

Is Greifswald a bubble?

Greifswald, which has only been district capital since 2012, feels isolated from such problems. Some feel that the city has not taken its role as capital seriously, Meerkatz says, while others confess that local politics is very Greifswald-centric, and that there is a disconnect between the town itself and the surrounding area. Greifswald, say several people, is a bubble.

Even with its Green mayor and its international flavour, Greifswald too has its gripes with the EU. The cultural affinity with Russia among older generations means that many are highly critical of Russian sanctions, Joachim Schmidt says. Both TTIP and the Common Fisheries Policy are also subject to public ire.

Most people here would identify as Pomeranians, rather than Europeans or even Germans, estimates Meerkatz. The Pomeranians, she says, are “maulfaul”, an uncommunicative bunch, but “when you get them, you really have them.” Yet if people are Pomeranian above all else, that does not mean they feel much affinity with their fellow Pomeranians on the other side of the Polish border. They are Vorpommern. German Pomeranians.

Old clichés and new phobiae

Indeed, the border remains a point of contention for many. Development on Usedom is one thing, while Greifswald, says radio98eins’ Louise Blöß, has a “disproportionately high” rate of bicycle theft, which plays into old clichés of Polish bike thieves. Joachim Schmidt, on the other hand, thinks that in some places, anti-Polish sentiment has been replaced by islamophobia.

There is, clearly, no single identity, no single position on Europe among Greifswalders. Yet perhaps that is fitting for a town whose Swedish history seems almost as important to it as its German present. A town whose university and cultural programme draws visitors from across the continent. A town which, for all its easy-going flair, remains nonetheless rooted in a politically frustrated area of Germany. Here, Europe is not perfect, but it is ubiquitous. Here, Europe does what Europe does best. It muddles on.

—

Kit Holden is a British journalist based in Berlin. He is a member of “Wir sind Europa” Basisgruppe.

Kit Holden is a British journalist based in Berlin. He is a member of “Wir sind Europa” Basisgruppe.

Photos: Josie Le Blond; Jule Halsinger; pixabay/hpgruesen